Vanadium steps into the spotlight as Queensland’s Lindfield Project fuels Australia’s clean energy charge with geology logistics and battery power to match

, , , , , , , ,

, ,

, ,

When it comes to the energy transition, not all batteries come wrapped in lithium. Beneath the baked earth of northwest Queensland, a different element is quietly taking centre stage — vanadium — and Adrian Buck, Principal Geologist at Measured Group, believes it’s poised to play a much bigger role in powering Australia’s renewable ambitions.

At the AusIMM Critical Minerals Conference 2025 in Perth, Adrian presented “Critical Minerals Group Lindfield Project Case Study: Geology, Exploration and Vanadium Resources,” co-authored with P. Kelly and S. Winter, detailing the geological foundations and development trajectory of Critical Minerals Group’s (CMG) Lindfield Vanadium Project — a project that’s steadily transforming the Eureka Ridge into a future hub of battery mineral supply.

A strategic discovery in Queensland’s critical minerals corridor

Located 70 kilometres north of Julia Creek, the Lindfield Project sits within the Toolebuc Formation, a vanadium-rich shale sequence extending across the Carpentaria and Eromanga Basins. “The geology here is special,” Adrian explained. “It’s a major Proterozoic basement high separating two basins, which has created the right structural and sedimentary conditions for vanadium enrichment.”

With direct access to the Flinders Highway, Mount Isa Rail System, and Townsville’s processing infrastructure, the project is strategically positioned within Queensland’s fast-growing battery and critical minerals corridor — part of the state’s long-term push to build sovereign energy supply chains.

A resource with substance and scale

Adrian’s presentation outlined how CMG’s methodical exploration has built a strong foundation of geological confidence. The project’s database now incorporates 95 exploration holes and 4,951 assay samples, spanning drilling campaigns from the 1960s through to CMG’s 2023 program. “We’re building on decades of data, but with modern tools and a sharper focus,” he said.

The results speak for themselves: as of April 2024, Lindfield hosts a JORC 2012-compliant resource of 713 million tonnes at 0.32% V₂O₅, with 3.4% alumina (Al₂O₃) and 130 ppm molybdenum (Mo). “It’s one of the largest undeveloped vanadium resources in Australia, and importantly, it’s sediment-hosted — giving us consistent mineralisation over significant thicknesses,” Adrian noted.

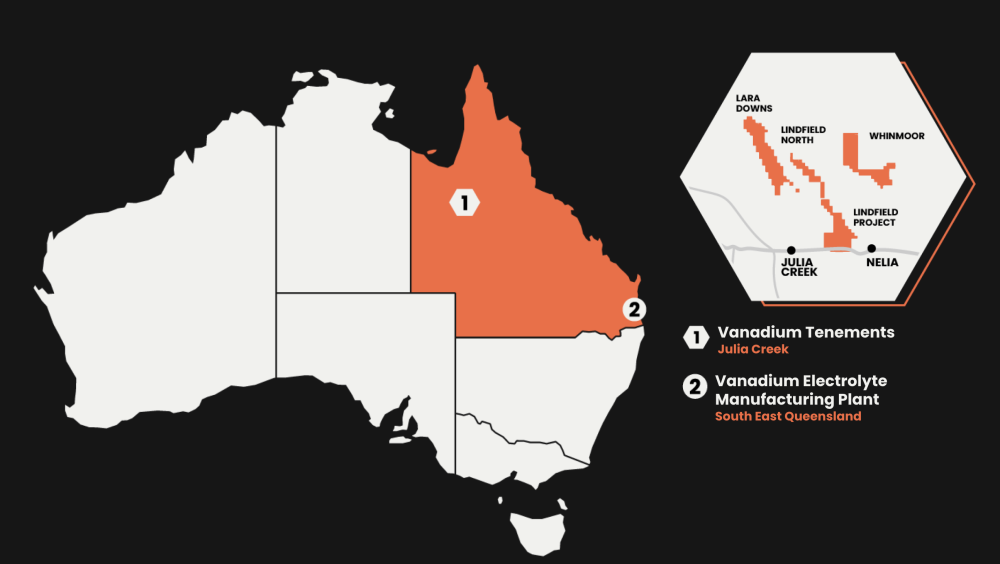

Map showing Critical Minerals Group’s vanadium assets in Queensland, including the Lindfield Project near Julia Creek and the proposed vanadium electrolyte manufacturing plant in South East Queensland.

Source: Critical Minerals Group

From exploration to production readiness

The project is now transitioning from study to strategy. CMG has completed its Project Scoping Study and is well advanced on Pre-Feasibility Study (PFS) work, paving the way toward development decisions. Adrian described the momentum as both technical and strategic. “We’re progressing at pace — not just to define the resource, but to de-risk it for long-term production and integration into Queensland’s emerging vanadium ecosystem.”

That ecosystem is gaining traction, with the state government backing new processing infrastructure, including a planned vanadium electrolyte manufacturing facility in Townsville. As Adrian pointed out, “Our proximity to transport, processing and export infrastructure makes Lindfield one of the most development-ready vanadium projects in the country.”

Why vanadium matters

Vanadium’s moment in the spotlight stems from its use in vanadium redox flow batteries (VRFBs) — long-duration energy storage systems ideal for grid-scale renewable integration. Unlike lithium batteries, VRFBs don’t degrade over time and can cycle indefinitely, making them a cornerstone of future energy storage networks.

“Vanadium isn’t competing with lithium — it’s complementing it,” Adrian said. “Flow batteries are built for stability, scalability and safety, and the vanadium we’re defining at Lindfield is exactly what those technologies need.”

A geologist’s long view

For Adrian, who has spent over two decades studying sedimentary vanadium systems around the world, Lindfield represents a rare intersection of geological science and industrial opportunity. “Queensland’s geology has always held the potential,” he reflected. “What’s different now is the global context — we’re finally seeing vanadium recognised for the strategic role it can play in renewable energy storage.”

As CMG prepares to release updated study results later this year, the industry’s eyes are on northwest Queensland. Beneath the quiet ridges of Toolebuc, a new chapter in Australia’s energy story is being written — one layer of vanadium-rich shale at a time.

In short: Adrian Buck’s case study of the Lindfield Project shows how world-class geology, modern exploration, and strategic infrastructure are aligning to put vanadium on the battery map — and Queensland firmly on the critical minerals frontier.