Empire’s titanium unicorn breaks the mould with free-dig ore, no ilmenite, and a flow sheet that rewrites the TiO₂ playbook

, , , , ,

, ,

, , ,

Forget ilmenite—sediment-hosted, hydrothermally-altered titanium system in Western Australia is flipping the script on how high-grade TiO₂ feedstocks are found—and how they’re processed.

At the recent RIU Sydney Resources Round-up, Empire Metals managing director Shaun Bunn gave a technically rich presentation that detailed how the company’s Pitfield Titanium Project could reshape the way the world sources high-purity titanium dioxide—without going anywhere near mineral sands or igneous rock.

“We’ve found something different—something we believe can change the titanium market,” Bunn told delegates. “There’s no ilmenite here. This is an orebody dominated by rutile and anatase in a weathered sandstone, and it’s been mineralised by a hydrothermal system that’s charged the entire basin.”

And that basin is enormous: 40 kilometres long, 10 kilometres wide, and up to 5 kilometres deep.

From drillhole to flowsheet

So far, Empire has completed over 200 drillholes—every one of them intersecting mineralisation from surface to end-of-hole. The company has defined an exploration target of 26 to 32 billion tonnes and is now homing in on the near-surface weathered zone, where free-digging, high-grade material can be recovered without drill-and-blast, crushing, or grinding.

“This isn’t mineral sands. There’s no need for oversize handling, crushers, or mill circuits,” said Bunn. “The material is soft, friable, and gravity-recoverable. And we’re not throwing anything away.”

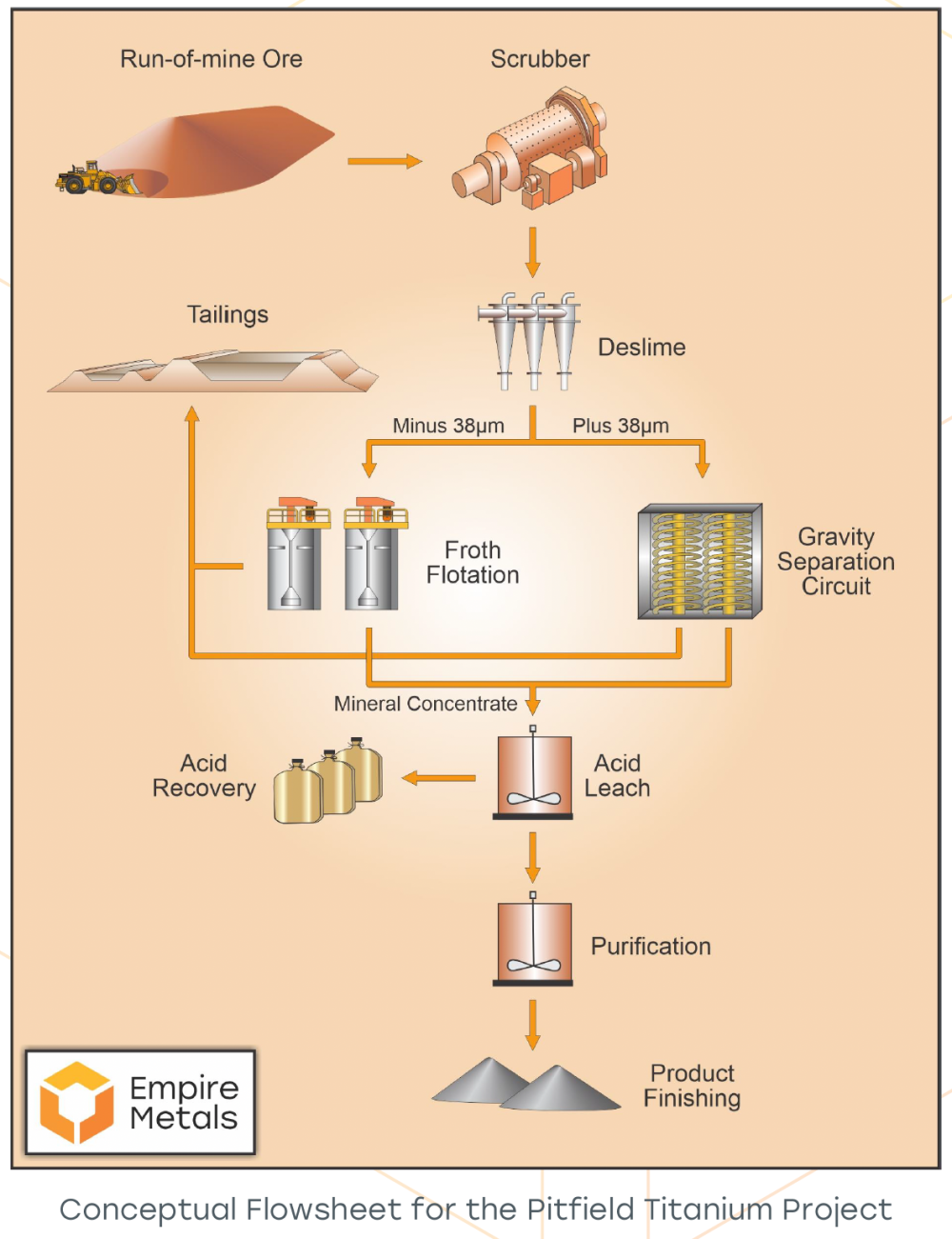

The Pitfield flowsheet, as outlined in the presentation, starts with scrubbing to break down kaolinite clay and de-slime the feed. A gravity circuit then separates the coarse rutile and anatase minerals, while flotation captures the titanium-rich fines typically discarded in kaolin processing. The concentrate is then subject to acid digestion to produce a semi-refined product suitable for pigment or metal feedstock.

Back in March, Empire announced it had successfully produced a 92 percent TiO₂ concentrate in early trials. The aim now is to refine that output even further to meet chloride-route pigment and titanium metal specifications.

Infrastructure, scale and upside

From an operational perspective, Pitfield is strategically located: 150 kilometres from Geraldton, with direct access to rail, high-voltage power lines, and the Dampier-to-Bunbury gas pipeline. The largest wind farm in WA is practically on the lease boundary.

“In terms of infrastructure, we’re blessed,” said Bunn. “We’re not building roads or stringing power. It’s all here.”

Bulk sampling has already been undertaken, with a 70-tonne metallurgical sample supporting scale-up of lab trials into a pilot-level program. Empire expects to deliver a maiden JORC resource before the end of Q3 2025 and is moving into early engineering study work concurrently.

While an ASX listing is under active consideration, Empire is currently listed on London’s AIM (LON: EEE) and has enjoyed strong performance—ranking as the second-best stock overall and top-performing mining stock on AIM in 2024.

What it means for METS

Pitfield is a case study in practical mining innovation: sediment-hosted titanium, gravity-first processing, free-digging ore, no crushing, no mill, and no tailings dams filled with fine clays. The potential implications for METS providers are vast:

-

Process equipment: scrubbers, gravity tables, flotation columns, and acid digestion systems

-

Bulk handling: free-dig material calls for efficient dozer, truck, and conveyor solutions

-

Sampling and assaying: clay-rich, weathered ore demands precision in sample prep and test work

-

Environmental tech: low-waste flow sheet opens doors for closed-loop processing innovation

-

Logistics: proximity to infrastructure simplifies integration with port and energy networks

In Bunn’s words, “We’re not just discovering titanium—we’re disrupting how it’s produced.”